Snakes are among the most common reptiles in the world, and can be found on every continent, except Antarctica. These animals will occasionally venture into the water to hunt for prey, or even just to move around their environments.

Generally, snakes can not breathe underwater. They are air-breathing reptiles, and can only stay underwater for a limited time before they have to resurface.

When a snake dives underwater, it holds it breath until it returns to the surface.

That said, some species of snakes, such as sea snakes, and certain water snakes, can hold their breath for considerable periods of time while submerged (read on to find out more).

Snakes Have Lungs and Breathe Air

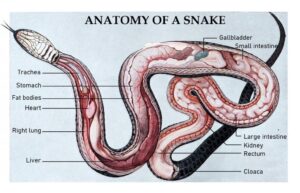

Like all reptiles, snakes have lungs, that they use to breathe air.

Due to their elongated bodies, snakes do not have lungs that are located side to side, like ours.

Instead, they have one shorter and one very long lung in a series. In most species, the left lung is the smaller one and is roughly 85% of the length of the elongated right lung.

Some species only have one elongated lung, and the smaller lung is absent.

The longer lung occupies around 30 percent of the body length in boas (Boidae), and as much as 80 percent of the body length in some colubrids (Colubridae) and elapids (Elapidae).

In many snakes, the smaller left lung is vestigial, and all gas exchange happens with the longer lung.

How Snakes Breathe

To breathe, snakes take air down into their lung (s). Once the air is in the lungs, oxygen from the air is then absorbed into the snake’s bloodstream. At the same time, carbon dioxide from the bloodstream is diffused into the air.

That said, it’s important to note that snakes do not possess a diaphragm, to move air in and out of their lungs, as mammals do.

Instead, they respire using their ribs.

In between each rib, are muscles that help force air out of the lungs.

To breathe in, the muscles contract, and air rushes into their lungs -and to breathe out, the muscles relax and, air leaves the lungs.

While underwater, snakes return to the surface periodically to replenish their oxygen stores and expel waste gases – with their lungs.

Some Snakes Can Stay Underwater for a Considerable Amount of Time

Although all snakes can swim, most snakes only swim at the water’s edge, or in shallow water. For this reason, they do not stay submerged for long periods.

However, many semi-aquatic snakes have adaptions that allow them to stay submerged for for a considerable period of time.

For example, Plain-bellied water snakes (Nerodia erythrogaster) have been observed submerged underwater for several minutes, and lying in wait for prey to approach.

Sea Snakes Can Hold Their Breathe for Longer Than Any Other Snakes

Sea snakes are the most aquatic snakes, and live in marine environments for most of their lives.

These snakes are highly adapted for their semi aquatic life and often dive to the sea floor to hunt – staying submerged for up to 30 minutes before returning to the surface for air.

Olive sea snakes (Aipysurus laevis) are known to spend up to two hours underwater before returning to the surface to breathe.

A few species of sea snakes can even stay underwater for up to 8 hours!

The Snakes Can Can ‘Breathe’ Underwater

Although sea snakes need to resurface to breathe air, some species have found ways to top up their oxygen levels while submerged.

A team of researchers analyzed the bodies of two blue-banded sea snakes (Hydrophis cyanocinctus) – and discovered a gill-like network of blood vessels in the animals’ heads.

This complex system of blood vessels is known as a modified cephalic vascular network (MCVN).

It is located just under a broad area of skin between the snout and the roof of the snake’s head.

While the MCVN is structurally very different from the gills of fish, its function is similar. It provides a large surface area packed with oxygen-depleted blood vessels.

The oxygen-poor blood in these vessels is able to absorb oxygen from the surrounding water – through the skin.

The blood oxygenated blood is then carried to the brain – very similar to how a fish’s gills work.

In this way blue-banded sea snakes use the top of their head, as a sort of gill, to breathe underwater.

This ‘skin breathing’ is known as cutaneous respiration, and is very unusual for reptiles, because their skin is thick and scaly.

That said ,blue-banded sea snakes still need to surface in order to breathe air, but the MCVN allows them to do so much less frequently than would otherwise be the case.

Can Snakes Drown?

Despite their various adaptions, snakes can drown.

If a snake gets into water where it can not surface for air, or otherwise get out of the water, drowning is a real possibility.

For example, if a snake is swimming in a pond, and gets entangled in a fishing net, the snake may drown if it is unable to reach the surface.

Conclusion

Snakes live in a wide variety of habitats, from deserts to marine environments.

Many snakes venture into the water, at least occasionally, to hunt, escape predators, or simply to move across different areas of their habitat.

Although all snakes can swim, snakes generally can not breathe underwater, and can only stay submerged for a limited amount of time before they have to resurface for air.

Some species of snakes are highly adapted for a semi-aquatic lifestyle, and can hold their breathe for several hours – before resurfacing to replenish their oxygen stores and expel waste gases.

Sources:

By Douglas Mader, M.S., DVM, DABVP. Snake Anatomy: Know your snake inside and out with this snake anatomy introduction. (PDF).

Guillaume Fosseries, Anthony Herrel, et al. Can all snakes swim? A review of the evidence and testing species across phylogeny and morphological diversity, Zoology, Volume 167, 2024, 126223, ISSN 0944-2006, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2024.126223.

Palci, A., Seymour, R. S., Nguyen, C. V., Hutchinson, M. N., Lee, M. S. Y., & Sanders, K. L. (2019). Novel vascular plexus in the head of a sea snake (elapidae, hydrophiinae) revealed by high-resolution computed tomography and histology. Royal Society Open Science, 6(9), 191099. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.191099

Hi, my name is Ezra Mushala, i have been interested animals all my life. I am the main author and editor here at snakeinformer.com.