If you’ve ever seen a skink flash across a sunny rock or slip under a pile of leaves, you know these little creatures can make you stop and think, “What exactly am I looking at?” They’re shiny, smooth, quick, and kind of mysterious.

Sometimes they look like a snake with legs. Other times they look like a sleek lizard. And every now and then someone sees one near water and thinks, “Wait, are these things amphibians?” So that brings us to the big question: are skinks reptiles or amphibians?

Skinks are reptiles, not amphibians. They have scales, they lay eggs with leathery shells, and they breathe air their whole lives. Nothing about them fits the biology of amphibians. Even though they sometimes get confused for amphibians because of their shiny skin or the way they hang around damp areas, skinks are 100 percent reptiles.

They have the same type of scales you see on other lizards, they regulate their body temperature like reptiles, and they develop on land rather than going through a tadpole-like stage.

Once you really look at their bodies and habits, the reptile identity becomes crystal clear.

Why People Mix Up Skinks With Amphibians

It’s pretty common for people to confuse shiny lizards with amphibians. The shine throws people off.

Skinks often have smooth, glossy scales that catch the light and make them look a little wet, even though their skin is dry.

Amphibians like frogs, newts, and salamanders usually have moist, soft skin. When someone sees a shiny skink, especially one with a blue tail or a bright stripe, their brain goes, “Moist skin means amphibian.”

But skink skin isn’t moist at all. It’s just naturally shiny.

Another big thing that confuses people is how fast skinks move.

Amphibians tend to hop or crawl, but skinks move in a low, sliding, almost snake-like motion that looks nothing like a frog or a salamander.

The smoothness of their movement makes people unsure what group they belong to.

And because many amphibians hide under rocks or logs, people assume anything hiding in the same places must be the same kind of animal.

But the truth is that skinks use those spots because they love warmth and protection, not moisture. Amphibians need dampness so they don’t dry out.

Skinks hide under things to warm up slowly or cool down quickly. They’re using the same real estate, but for totally different reasons.

What Makes a Reptile a Reptile?

To really understand why skinks belong to the reptile family, it helps to look at what makes reptiles reptiles in the first place.

Reptiles share a few very specific traits:

-

They have dry, scaly skin.

-

They breathe air through lungs their whole lives.

-

They use the environment to regulate their body temperature.

-

They lay eggs with leathery shells or give birth on land.

-

They never go through an aquatic larval stage.

Skinks match every single one of these traits. Their scales aren’t just for show. They protect the body, reduce water loss, and help the skink move smoothly through grass and dirt.

Their entire respiratory system is built for air breathing, not water breathing. Their babies hatch on land and look like tiny versions of the adults from the very first moment.

There’s no tadpole stage, no gills, no metamorphosis. Everything about them screams reptile.

What Makes Amphibians Amphibians?

Now compare that to amphibians. Amphibians have:

-

Moist, permeable skin.

-

A need for water to keep their skin hydrated.

-

Eggs laid in water or very damp environments.

-

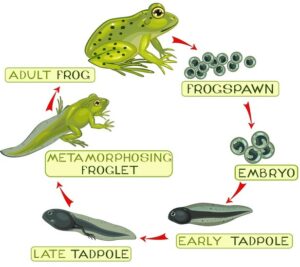

Larval stages like tadpoles or water-breathing juveniles.

-

A major body change as they mature.

Skinks fit none of that. Not a single piece. Their skin isn’t moist. Their eggs don’t need water. Their babies don’t swim. They don’t breathe through their skin.

And they don’t transform from one body shape into another.

If you lined up a skink egg next to a frog egg, you’d see immediately that they come from two completely different biological worlds.

How Skink Eggs Work and Why That Makes Them Reptiles

Skink eggs are one of the biggest giveaways. Reptile eggs have a leathery shell that helps protect the developing baby from drying out while still letting oxygen in.

Amphibian eggs are jelly-like, soft, and laid in water or super moist areas. Skink eggs are nothing like amphibian eggs. They’re firm, laid in secure nests on land, and rely on warmth from the environment.

Many skinks even guard their eggs, warming them with their body heat or wrapping around them to keep them safe.

Amphibians almost never do that. Their reproductive strategy is totally different. Frogs lay a huge number of eggs in water and hope some survive.

Skinks lay fewer eggs, but they invest more in protecting them.

Even the development of the embryo inside the egg is reptile-like. The baby skink forms bone, scale, muscle, and lung development early on.

When the baby hatches, it already knows how to breathe air, walk, hunt, and hide. That’s classic reptile behavior.

Do Skinks Ever Live in Water Like Amphibians?

Skinks sometimes hang out near damp areas or retreat into moist leaf piles on hot days. But this isn’t because they need water like amphibians do.

It’s simply because they’re trying to avoid overheating or drying out in extreme heat. Reptiles can overheat easily, so they look for shade, moisture, or cool hiding places.

Amphibians go to water so they don’t dry out. Skinks go to water-adjacent spots because they’re adjusting their body temperature.

Totally different reasons, but the behavior looks similar, which is why people sometimes assume they are amphibians.

Some species, especially tropical skinks, do swim or float when escaping predators. But swimming doesn’t make an animal an amphibian.

Plenty of reptiles swim, including snakes, iguanas, crocodiles, and monitor lizards. That doesn’t change their category.

Why Skinks Look So Different From Other Lizards

This is where things get interesting. Skinks look a little unusual. Their bodies are smooth and elongated. Their heads are narrow.

Their legs are short, and in some species the legs are so tiny they look almost useless. A few skink species even look like they hardly have legs at all.

When you combine that body shape with their shiny scales, it can be confusing for anyone trying to figure out what they’re related to.

They look a bit like snakes and a bit like salamanders. Snakes are reptiles, salamanders are amphibians, and skinks sit somewhere visually in the middle.

The key difference is the structure of their skin. Reptile scales are made of keratin, the same material as your fingernails.

Amphibian skin is soft, thin, and has glands that keep it moist all the time.

If you touched a skink and then a frog, you’d feel the difference right away. Skinks are never slimy. Amphibians usually are.

How Skink Breathing Shows They Are Reptiles

Skinks breathe only through their lungs. Amphibians breathe in different ways depending on their life stage.

Tadpoles often use gills. Newly transformed frogs use lungs but also breathe through their skin.

Skink lungs are well developed, and they use them from the moment they hatch until the end of their lives.

They can’t breathe underwater. They can’t absorb oxygen through their skin. If a skink is underwater for too long, it drowns.

That alone separates them from amphibians in a big way.

What Skinks Eat and How Their Diet Shows They’re Reptiles

Skinks eat insects, worms, small invertebrates, and sometimes fruit or vegetation. Their jaws are built to crush or hold prey, not gulp things whole the way frogs do.

Amphibians usually need their prey to move so they can strike at it. Many frogs use sticky tongues to catch insects.

Skinks don’t have a sticky tongue. They just bite and eat like most reptiles.

The way they digest food, control their energy, and move through their environment all match the reptile blueprint perfectly.

A Closer Look at Skink Skin and Why It’s Not Amphibian Skin

Skink scales are tightly overlapped to hold in moisture. Amphibian skin leaks moisture constantly, which is why amphibians must stay wet. If a frog dries out, it dies.

If a skink dries out, nothing happens. It just keeps on living normally.

The scales also act like armor. You can hear a soft rustling sound when a skink moves through dry leaves because the scales brush against the debris.

Amphibians don’t make that sound because their skin is too soft.

Are There Any Amphibian-like Reptiles That Might Confuse People?

Some reptiles, like certain legless lizards or slender snake-like species, resemble amphibians at first glance. But biologically they’re still reptiles.

Skinks fall into this category. Their body shape tricks your eyes, but their biology never lies.

Why Skinks Never Go Through Metamorphosis

If you ever find a baby skink, it looks exactly like a tiny version of the adult, just brighter or more vivid in color. Amphibians always go through a major body change.

Tadpoles grow legs. Salamanders lose gills. Frogs reshape their skull and body to match adult life.

Skinks don’t do any of that. They hatch as miniature adults, which is one of the clearest signs they are reptiles.

Why Skinks Prefer Warmth and What That Says About Their Identity

Reptiles are cold blooded, so they rely on the sun, rocks, and warm surfaces to regulate their body temperature.

Amphibians use water and shade more than sunlight because their skin dries out easily.

Skinks love sunbathing. They will sit on warm stones, concrete, fallen logs, or even metal surfaces to warm up.

You’ll never see an amphibian basking like that for long. Amphibians overheat fast. Skinks warm up slowly, then move off to hunt with extra energy.

Why You See Skinks in Gardens and Yards but Not Amphibians in the Same Way

Skinks love dry leaves, warm walls, sunny flowerbeds, woodpiles, cracks in bricks, and warm concrete.

Amphibians would die in most of those places unless it had just rained. Amphibians stick to ponds, shaded soil, mud, and wet forest floors.

If your yard is dry, sunny, and warm, skinks will thrive. Amphibians won’t.

Conclusion

Skinks confuse people because of the way they look and move, but once you break down their biology, the answer becomes completely clear.

They are reptiles, not amphibians. They have scales, dry skin, air breathing lungs, land-based eggs, and babies that hatch as tiny versions of the adults.

They don’t rely on water to survive and they never go through a tadpole stage. Everything about their life, body, and behavior fits the reptile world perfectly.

So the next time you see a shiny skink racing across a warm surface or slipping into a crack in the wall, you can feel confident knowing exactly what you’re looking at.

It’s not an amphibian pretending to be a lizard. It’s not some halfway creature living between two worlds.

It’s a full reptile living its best reptile life, sprinting, hiding, warming up, hunting bugs, and doing everything its lineage has done for millions of years.

Hi, my name is Ezra Mushala, i have been interested animals all my life. I am the main author and editor here at snakeinformer.com.