If you’ve ever watched a lizard sitting on a warm rock and then looked up to see a bird perched on a branch doing almost the same thing, it’s easy to wonder if they’re somehow connected.

They both lay eggs, they both look a bit ancient, and they both move in these sharp, quick ways that make you think they’ve been around forever. So are they connected at all? Are lizards related to birds?

Lizards and birds share very old reptile ancestors, but they aren’t directly related. Lizards fall under a group called Lepidosauria, which includes snakes. Birds come from Archosauria, the same group that includes dinosaurs and crocodiles. That means birds are actually closer to dinosaurs and crocodiles than to any lizard on your wall.

It’s one of those strange things about evolution. The gecko climbing your window and the sparrow in your yard came from the same distant reptile line, but their paths split hundreds of millions of years ago.

How The Reptile Family Tree Split Apart

To see how lizards and birds connect, you have to go way back, over 300 million years. Early reptiles back then were small, scaly animals living in warm, swampy places.

As time went on, those early reptiles split into two major lines.

One became the Lepidosaurs, which eventually turned into lizards, snakes, and the tuatara.

The other became the Archosaurs, which later split again into crocodiles on one side and dinosaurs on the other. Birds eventually came from the dinosaur side.

So birds didn’t come from lizards. They came from small, feathered dinosaurs. Lizards and birds are more like very distant cousins who haven’t shared the same path in a very long time.

What Lizards And Birds Still Share Today

Even though their connection is ancient, lizards and birds still share a few traits from their reptile ancestors.

They both:

- Lay eggs with shells to protect their babies.

- Have scales, though birds turned most of theirs into feathers.

- Have similar bone structures in parts of the skull and limbs.

- Rely on external heat (at least partly, before birds became warm-blooded).

If you look at a chicken’s legs, the scaly skin is a clear reminder of where birds came from.

They didn’t lose their scales. They just changed most of them into feathers so they could survive in new ways.

The Dinosaur Link That Changed Everything

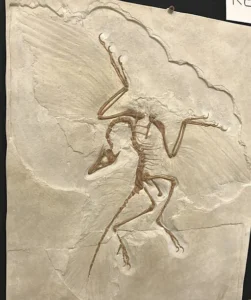

For a long time, people thought birds didn’t really fit anywhere. Then fossils changed that idea completely.

Archaeopteryx, discovered in the 1800s, had feathers like a bird but teeth and claws like a small dinosaur. That one fossil showed the link. Birds came from theropod dinosaurs, the group that includes Velociraptor and even T. rex.

That means birds aren’t just related to dinosaurs. Birds are dinosaurs.

Crocodiles are their closest living relatives. Lizards, even though they’re reptiles too, aren’t from that line at all.

So when you watch a robin hopping around your yard, you’re looking at a small, modern dinosaur, not a cousin of lizards.

How Evolution Sent Them In Different Directions

Even though they started with similar bodies, lizards and birds changed in completely different ways.

Lizards kept their scales, stayed cold-blooded, and adapted to life on the ground, in trees, in deserts, and almost anywhere else. They crawl, climb, dig, and glide, but they never became full-on fliers.

Birds changed almost everything they had. Scales became feathers. Front legs became wings. Their bones became lighter. Their bodies warmed up so they could stay active and fly long distances.

It’s like two people starting with the same ingredients in a kitchen and ending up making two totally different meals.

Are Birds Considered Reptiles?

This surprises a lot of people, but yes, birds are considered reptiles in modern science.

That’s because scientists group animals based on ancestry, not looks. Since birds came directly from dinosaurs, and dinosaurs were archosaurs, birds fall into the reptile group too.

So birds didn’t stop being reptiles. They just became a very advanced type of reptile. The kind with feathers, warm blood, and the ability to cross oceans.

What Fossils Tell Us About Their Split

Fossils make the story pretty clear.

The first lepidosaurs, the ancestors of lizards and snakes, appeared around 250 million years ago. Around the same time, the archosaurs split off, turning into crocodiles on one side and dinosaurs on the other.

By the time dinosaurs ruled the planet, lizards were already around as small, quick creatures hiding under rocks and in trees.

When the dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago, lizards survived because of their small size and flexibility. Some small dinosaurs survived too. Those dinosaurs are now birds.

So their connection exists, but it’s incredibly old.

Why Birds Are Closer To Crocodiles Than To Lizards

It sounds strange, but birds share more in common with crocodiles than with lizards.

That’s because both birds and crocodiles are archosaurs. They share deep traits, including:

- Four-chambered hearts.

- Nesting behavior and egg guarding.

- Similar skull openings and jaw structures.

Lizards have three-chambered hearts and totally different skull shapes. Even their brains work differently.

So if you lined up a crocodile, a bird, and a lizard, and asked which two were closest relatives, most people would guess wrong.

The bird and the crocodile are the closest pair.

How They Survived When Dinosaurs Didn’t

When the asteroid hit 66 million years ago, most dinosaurs died, but lizards and the ancestors of birds survived for different reasons.

Lizards survived because they were small, spread out, and able to live on very little food.

Birds survived because some were small, able to fly, and able to eat a wide range of foods, including seeds and insects.

Their survival shows how different branches of reptiles found different ways to make it through a major disaster.

What About “Flying Lizards”?

Some lizards can glide, like the Draco lizard. They spread their ribs to float from tree to tree.

It’s easy to think they’re related to birds, but they aren’t. Their wings are just stretched skin held up by ribs, not feathers or wing bones like birds.

This is a good example of convergent evolution, where two animals solve the same problem in different ways.

Why People Still Think Lizards And Birds Are Related

People often connect them because some bird features still look reptile-like.

- A chicken’s feet look like a lizard’s feet.

- Some birds move their heads like reptiles.

- They both lay eggs.

- They both rely on sunlight in different ways.

Those little hints make their deep connection show through, even though they split long before the first dinosaur appeared.

A Simple Way To Picture Their Relationship

Here’s an easy way to think about it:

- Around 300 million years ago, early reptiles appeared.

- Around 250 million years ago, they split into two big groups: lepidosaurs (lizards and snakes) and archosaurs (crocodiles, dinosaurs, and later birds).

- Lizards kept the original reptile style.

- Dinosaurs changed, grew feathers, and became birds.

So birds aren’t descended from lizards. They just share the same very old roots.

Reptiles Aren’t Just One Type Of Animal

People used to think reptiles were slow, cold, and simple. But birds changed that idea completely.

Birds are reptiles that became warm-blooded, fast, smart, and able to fly.

Lizards show another side of reptiles. They’re patient, adaptable, and able to survive almost anywhere.

Put together, they show how wide and flexible the reptile family really is.

Conclusion

Lizards and birds might seem like totally different animals, but they both came from the same early reptiles that lived hundreds of millions of years ago.

Still, they aren’t close relatives. Lizards are on the lepidosaur branch. Birds are on the archosaur branch with crocodiles and dinosaurs. That makes birds much closer to crocodiles than to any lizard.

So the next time you see a lizard warming up on a rock and a bird preening nearby, remember you’re looking at two survivors from the same ancient family. One stayed on the ground, and the other learned to fly.

Hi, my name is Ezra Mushala, i have been interested animals all my life. I am the main author and editor here at snakeinformer.com.